It’s hard for me to review Gerald’s Game without going into my complicated relationship with Stephen King (this is what journalists call “an awful lede”). I started reading King when I was about 10 and his were among my first “adult” novels. The Shining, in particular, had a devastating affect on my not-yet-fully-developed mind. Beyond the ghouls and ghosts, it was my first exposure to a concept less fantastic but far more disturbing – the crushing unhappiness of adulthood.

Then I sort of grew out of King, eventually becoming frustrated with the same flaws that bother everyone about his prolific catalogue: incredible premises botched with goofy supernatural endings, a general boorishness, the fact that every single one of his male characters share the exact same misanthropic voice. King’s work is in the middle of a popular and critical renaissance and it’s a lot cooler to like his writing than it was 10 years ago. I keep trying to embrace him again, to appreciate his unrivaled knack for genre storytelling, but I just can’t really do it. And Gerald’s Game is a pretty good example why.

Director/co-writer Mike Flanagan’s Netflix film is, from what I understand, a pretty faithful adaptation (I haven’t read the book). I think if you’re reading this review, you most likely know the story’s hook (revealed about 20 minutes in), but, if not, *MAJOR SPOILERS* ensue.

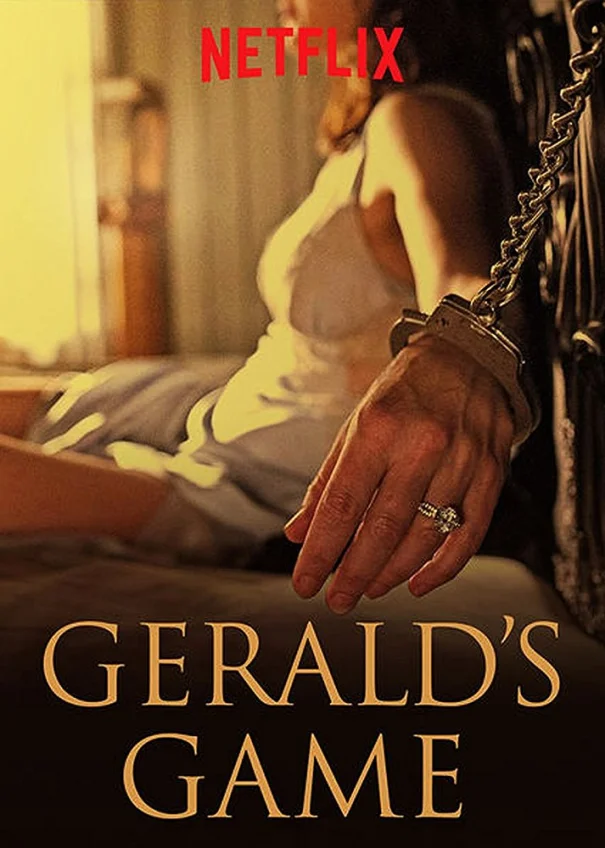

Jessie (Carla Gugino) and Gerald (Bruce Greenwood, distracting in an overly showy performance) are a middle-aged couple stuck in a rut. As Gerald’s Game starts, they are heading out to Jessie’s family’s lake house in an attempt to re-energize their floundering marriage. For Gerald, that means a bottle of Viagra and kinky handcuff sex. Rather unfortunately for Jessie, Gerald unexpectedly suffers a heart attack during their awkward attempt at rough sex, and she is left chained to the bedposts in a remote getaway without food, water, or any hope of salvation.

It’s an intriguing set-up, but obviously not particularly cinematic – the majority of the story follows a solitary character trapped in bed. By far the best and most interesting aspect of Gerald’s Game is how Flanagan transcends these limitations. Flanagan dramatizes Jessie’s inner monologues and mental debates with her recently deceased husband, filming conversations that take place entirely in her mind as if they were really happening. Frequently, multiple hallucinatory versions of Gugino and Greenwood stalk the stage, arguing with one another and presenting differing opinions. It’s very cool and makes a potentially claustrophobic film surprisingly lively and engaging.

But King’s usual Achilles’ heel(s) are all too prevalent (and I won’t even stoop to repeating some of the most eye-rolling dialogue). A major part of the story – which, admirably, is less about her attempts to escape her physical predicament and more about how the scenario forces her to re-examine her life – involves Jessie coming to terms with the fact that she was molested by her father as a child. But, rather than challenging or uncompromising, this material is just more run-off from King’s lucrative assembly line of contrived suffering. As I wrote in my review of It, “King, a white, Christian-raised male, has always seemed particularly zealous to inflict cruelties on female and black supporting characters under the guise of social commentary.” Jessie’s exploitation is not particularly nuanced or provocative. The 12-year-old version of her character exists solely to be abused, simply because King wants his beach read to have a creepy, pseudo-psychological strands.

Gerald’s Game also has a wildly unnecessary supernatural element, one which Flanagan seems obliged to include, though the director does a nice job of shunting it to the margins for most of the movie. Unfortunately, and inexplicably, after Gerald’s Game comes to a gory, unforgettable, and completely fitting ending, Flanagan tacks on a stupendously awful 10 minute epilogue that races through a continuation of some ludicrous mumbo jumbo about a freakish character named The Moonlight Man (played by The Giant from Twin Peaks), who worst of all, turns out to actually be real. I feel genuinely bad for anyone who was more engaged with the film than I was, as this is one of the worst endings I’ve seen on a decent movie in years.

Gerald’s Game is Stephen King through and through, for better and for worse.