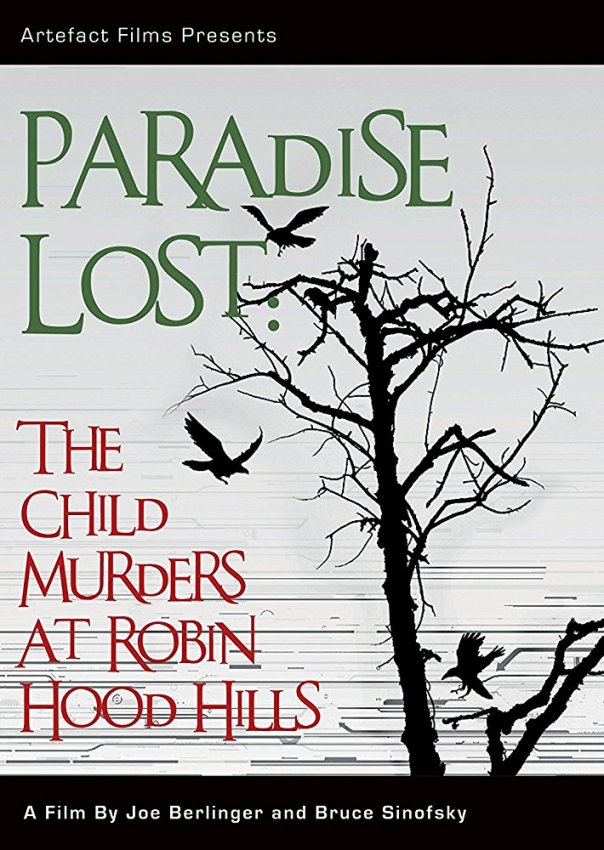

Paradise Lost, an HBO documentary which garnered significant critical acclaim, opens with some of the most disturbing crime scene footage ever included in a widely-viewed documentary. The videos show the bodies of three 8-year-old boys, residents of ultra-rural West Memphis, dead and desecrated on a wooded bank. It’s a jaw-dropping, stomach-churning opening, and one which sets a deliberate tone: Paradise Lost is not a salacious true crime saga, not a murder case repackaged as a Must-See TV mini-series or a beach read. This is a film about an unimaginable crime, the unimaginable grief it caused, and the search for answers.

Filmmakers Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky do a thorough job following the trials of three teenage boys accused of the murders in this two-and-a-half hour doc. As they interview the victim’s families, the accused, the accused’s families, both legal teams, community members, and incorporate quite a bit of courtroom footage, several themes emerge. While the prosecution has some key bits of evidence – a confession, a possible murder weapon, a motive tied to the country’s Satanism hysteria – none of them really hold up to scrutiny. But the community, angered and terrified and mourning, are desperate for the retributive justice and closure of a conviction. Paradise Lost is not a film of easy resolutions, and viewers may find themselves turning over its conflicting aspects for days: unscrupulous police procedures, revealing comments, inexplicable inconsistencies.

For modern audiences, weaned on polished Netflix docs and exhaustive investigative podcasts, the structure of Paradise Lost may occasionally frustrate. Aside from a few intertitles, Berlinger and Sinofsky employ a cinéma vérité approach: we never see them, in fact don’t even hear them asking questions, and there is no narration, re-enactments, or fancy production values. Deliberately eschewing these handy tools (or tricks, perhaps), there are odd narrative quirks, like key details introduced late in the film or seemingly important points on which the filmmakers never follow up.

Unexpectedly, Berlinger and Sinofsky’s finest accomplishment is the extraordinary snapshot they capture of West Memphis at the end of the 20th century. In parsing this tragedy, which so deeply impacted the community, a vivid picture of West Memphis emerges. The town’s anger, pride, confusion, empathy, all of its virtues and repressions, are present in the idle comments and perspectives shared in interviews, in the establishing shots of isolated churches and modest homes. To watch Paradise Lost is to inhabit a very specific time and place, and that is surely one of the most humanistic and lofty goals to which a documentary can aspire.