Conventionally speaking, Blade Runner is a bit of a mess. You can see why critics and audiences had mixed reactions to its original release: the plot is hazy and muddled, the characters are cryptic and inscrutable, and director Ridley Scott keeps us at a distance from the film’s emotional core. Blade Runner is a chilling piece of ‘80s new-wave futurism, a film easier to feel than understand or explain.

Very loosely adapted from Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Blade Runner takes place in Los Angeles in a 2019 that must’ve once sounded very far away. Most humans have emigrated to colony planets, and those left behind scurry like ants in a massive, industrialized cityscape of abandoned skyscrapers and overflowing trash. Scott, in one of several less than subtle choices, shoots the film almost entirely at night and under a steady sheet of pouring rain (crumbling apartment buildings are so sodden that you can push your arm through the soggy walls).

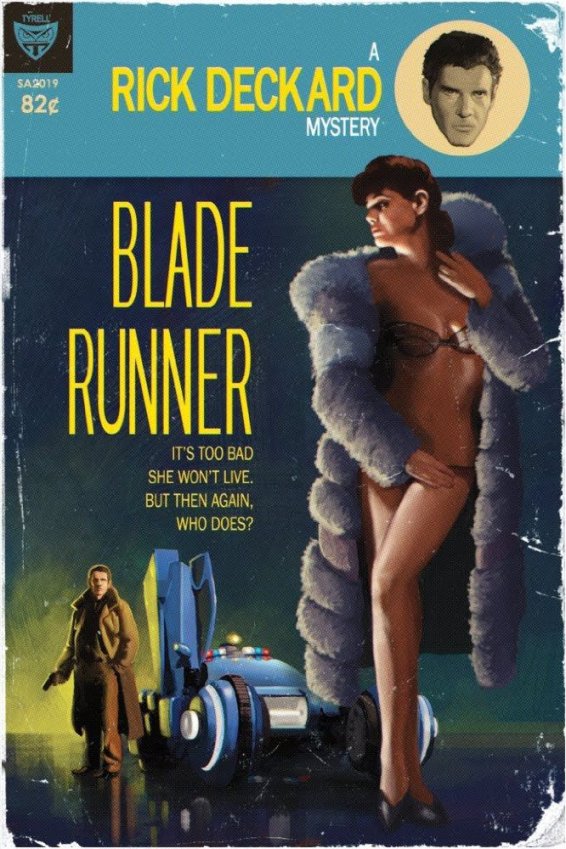

An omnipresent blimp patrols the skies, ostensibly to display advertising, but also scanning the city with restless, probing searchlights. Thanks to radiation fallout (I think?), a good deal of the population are little people. Garish neon lights illuminate the streets, and the flying cars, instead of cool and imposing, all look like used Mazdas. Amidst all this grime and shadow, Harrison Ford plays Rick Deckard, a retired “blade runner” (cops who hunt down and terminate rogue androids, called replicants) dragged back in for a dangerous job that involves capturing highly advanced replicants.

Blade Runner‘s universe is mysterious and mesmerizing. The story and characters are lifted from film noir; Deckard, our disgraced hero, is led into trouble by a femme fatale, his dangerous line of work, and, most of all, the heartless, fatalistic nature of existence. But Scott has taken the elements of noir, so dark and brooding, and laid them over a science-fiction background. In the hands of a light-hearted director like George Lucas, sci-fi is a product of whimsical optimism, hope for the future and nostalgia for the past. Needless to say, that is not the philosophical milieu in which Blade Runner operates, and the film’s bleak viewpoint had a huge hand in shaping the last 30 years of speculative film.

All films which take place in future time periods are inherently hypothetical: Children of Men wonders what life would be like without human reproduction, Escape From New York posits Manhattan as an inescapable prison for our worst criminals, etc. But, what Blade Runner captures perhaps more effectively than any of these films, is the melancholy sadness which accumulates like dust on a previous generation’s projection of the future. The characters in Blade Runner seem acutely aware of their wayward, hypothetical state of being – they act like people trapped in a bygone dream which will never come true. They are confused about themselves and their role in the world, grasping only their futility and insignificance. Watching them go through the motions is touching, but very sad, like discovering an old exhibit from the World’s Fair and feeling overcome with a sense of inexplicable loss.

At least, this is my experience with the film. Blade Runner is certainly not famous for its performances, confusing plot (how does a movie with so much exposition make so little sense?), or stilted action scenes, but rather for the spell it conjures on the viewer. Presumably, this will vary. But it’s clear that with Blade Runner, Ridley Scott struck a very specific and haunting tone, a feat he accomplish via masterful use of cinematography, set design, and score. This is one of the most visually accomplished and influentially stylish films ever made, with its unforgettable depiction of a dehumanized city resembling a gigantic computer chip that has fallen into a dirty gutter. The music, composed by Vangelis, is soulful and enigmatic, the perfect match for Blade Runner’s introspective despair.

Forget the horrendous narration. Ignore the often incomprehensible storyline, which fans have bent over backwards to rationalize. Don’t worry about whether or not Deckard is a replicant, since the subtext isn’t particularly well fleshed out anyway. Turn out the lights and just let Blade Runner work its strange magic.