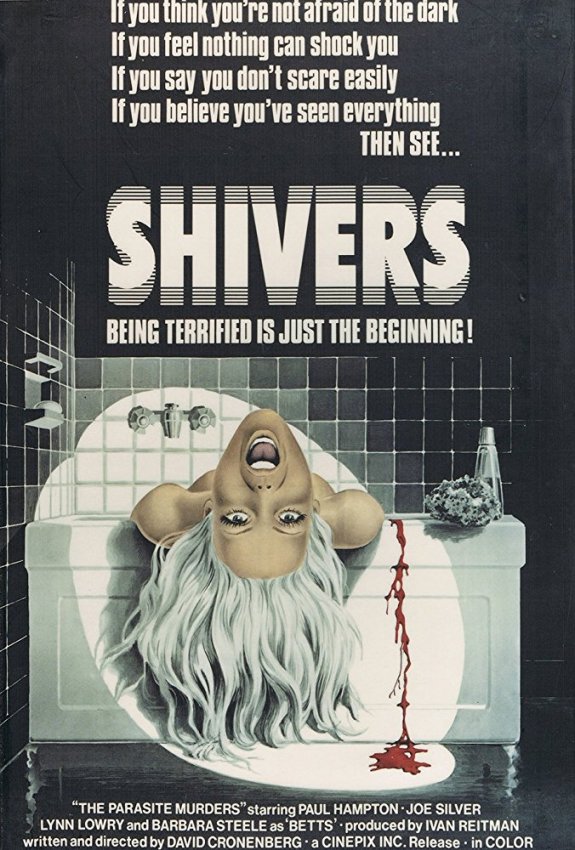

Shivers is not one of David Cronenberg’s best known films, nor does it have the cult following of a Scanners or Videodrome. That shouldn’t be the case: this lean, mean horror thriller is as stunningly fierce as it is wickedly smart.

In one of his earliest features, Shivers finds Cronenberg embracing a pulpier style than his later work, meaning the film is jam-packed with gratuitous nudity, jump scares, and elaborate horror set pieces (including a gleefully nasty bathtub scene which undoubtedly influenced Wes Craven). The result is an exploitation masterpiece that sacrifices none of the provocative insights of the auteur’s later work. In fact, in a rather clever example of having your cake and eating it too, the cheap thrills in Shivers are the means by which Cronenberg furthers his thematic interests. Shivers‘ lurid excesses are fully intertwined with its social commentary.

Shivers opens with a promotional video introducing us to the luxurious, state-of-the-art Starliner Towers, an imposing residential high-rise located on an island near Montreal. The Starliner boasts its own restaurant, swimming pool, and other amenities, including some of the most garish ‘70s decor ever committed to film. Fortunately, there’s also an in-house medical facility, which comes in handy when a highly contagious venereal virus starts attacking the building’s residents, turning them into sex-crazed pleasure junkies.

The premise (which bears many similarities to J.G. Ballard’s High-Rise, a novel released the very same year and recently turned into a fantastic film by Ben Wheatley) is an excellent one. Setting the action in a relatively isolated building establishes clear challenges and restrictions for the characters. It’s also a perfect opportunity to critique capitalism, consumer technology, and the soulless excesses of the Me Generation.

Our central protagonist is Dr. Roger St. Luc (Paul Hampton), a square-jawed physician looking the part of the classic male authority figure who saves the day with a combination of pragmatic intelligence and burly masculinity. This is, of course, a set-up for Cronenberg to reveal St. Luc as an inept, blustering moron. The story also follows St. Luc’s doting assistant Forsythe (Lynn Lowery), wise-cracking medical colleague Rollo Linksy (a fantastic Joe Silver), and the Tudors (Allan Kolman and Susan Petrie), a young married couple. Mr. Tudor is one of the virus’s first hosts, but the unquestioning way in which his wife and secretary react to his bursts of cruel hostility suggest that he was a creepy asshole long before a slippery little slug crawled into his body.

In typical Cronenberg fashion, the characters don’t really behave like recognizable humans. Shivers has its share of logical inconsistencies; for example, the residents certainly don’t act like their building is in the midst of a sensational murder investigation (Shivers opens with an act of stark violence). Yet, their antipathy and inhumanity is deliberate (and bleakly funny). Cronenberg depicts the building’s population as perverted, horny deviants even before the infection begins to take over.

“Sex is the invention of a clever venereal disease” reads a refrigerator magnet glimpsed in the background while Rollo Linsky munches on a pickle. The message is a thematic key to Shivers, if not Cronenberg’s entire filmography. For Cronenberg, the world is perhaps most easily viewed as a particularly lively and putrid petrie dish. When the characters in Shivers become infected, they simply lose the few inhibitions on which they had previously managed to hold a most tenuous grasp. At the film’s onset, the Starliner Towers are already beset with torrid affairs and decadent sexuality (Mr. Tudor is apparently cheating on his wife with a 19 year old; a 70-something bachelor spends his time talking to bored housewives about the restorative power of “megavitamins” and then brags to the doctor about his sexual conquests with these young ladies).

The last 20 minutes of Shivers pushes the movie beyond effective, modest horror and into bonafide classic status. With the virus now a full-fledged endemic and the residents freely enacting their darkest sexual desires, Dr. St. Luc, who looks as though he would blush at anything other than the missionary position, stumbles through the plague-infested Starliner, taunted by visions of homosexuality, sadomasochism, pedophilia, and incest. Cronenberg is unsparing and relentless: St. Luc is surely a repressed, obsolete fool clinging to an outdate prurience, but the behavior of the infected residents is unabashedly nightmarish. There’s nothing comforting in either direction.

The sequence retains its provocative power and mounting dread even today, and Cronenberg captures it with the audacious clarity of a young artist tapping into directly into his own fiendish subconscious. It’s a barrage of surreal and unsettling imagery, perhaps best surmised by an exchange in which the recently infected Nurse Forsythe delivers the following haunting speech to her paramour, St. Luc.

“Roger, I had a very disturbing dream last night. In this dream I found myself making love to a strange man. Only I’m having trouble you see, because he’s old…and dying…and he smells bad, and I find him repulsive. But then he tells me that everything is erotic, that everything is sexual. You know what I mean? He tells me that even old flesh is erotic flesh. That disease is the love of two alien kinds of creatures for each other. That even dying is an act of eroticism. That talking is sexual. That breathing is sexual. That even to physically exist is sexual. And I believe him, and we make love beautifully.”

Suddenly, a writhing, bloody parasite starts worming its way out of the nurse’s mouth. Is St. Luc more threatened by the parasite, or by the frank confessional manner with which this suddenly empowered young woman speaks about sexuality and eroticism?

Either way, our supposed hero punches Forsythe in the face, gags her mouth, and throws her over his shoulder, presumably under the guise of dragging her to safety. Watch the film to see just how well that goes for the good doctor.